The Herschel Space Observatory was launched on May 14 2009 and operated for nearly four years. It carried the largest and most powerful infrared telescope ever flown in space, and three sensitive scientific instruments which had to be operated at temperatures close to absolute zero. Herschel’s observations finished on April 29 2014 when the tank of liquid helium used to cool the instruments finally ran dry, but scientific work on the data will continue for many years. By the end of its life, Herschel had collected a huge amount of data, and its observations are helping astronomers to understand the Universe – particularly how stars form and how galaxies grew and evolved over cosmic time.

The Herschel Space Observatory was launched on May 14 2009 and operated for nearly four years. It carried the largest and most powerful infrared telescope ever flown in space, and three sensitive scientific instruments which had to be operated at temperatures close to absolute zero. Herschel’s observations finished on April 29 2014 when the tank of liquid helium used to cool the instruments finally ran dry, but scientific work on the data will continue for many years. By the end of its life, Herschel had collected a huge amount of data, and its observations are helping astronomers to understand the Universe – particularly how stars form and how galaxies grew and evolved over cosmic time.

Herschel was the first space observatory to observe from the far-infrared to the submillimetre waveband, unveiling the mysterious hidden cold Universe to us for the first time. Its data tap into previously unexploited wavelengths, seeing phenomena out of reach of other observatories, at a level of detail that has not been captured before, allowing us to study otherwise invisible dusty and cold regions of the cosmos, both near and far.

The telescope’s primary mirror was 3.5 m in diameter, more than four times larger than any previous infrared space telescope and almost one and a half times larger than that of the Hubble Space Telescope.

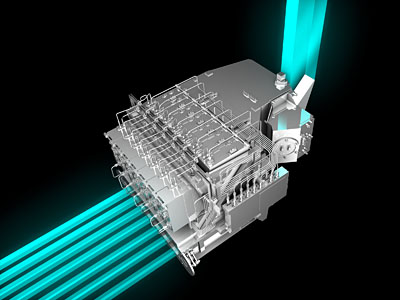

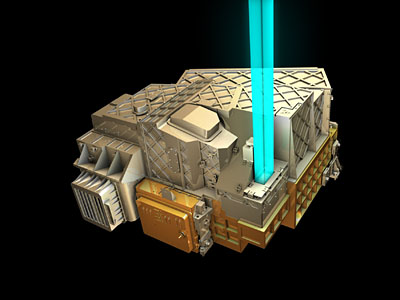

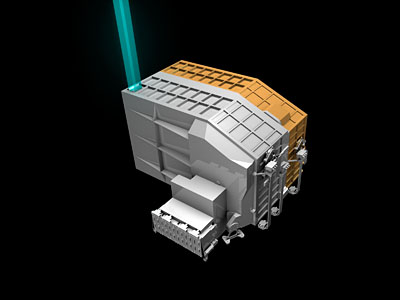

The satellite consisted of four main parts. The telescope, the payload (the instruments and the cryostat which cooled everything), the service module (electronics, satellite pointing, and communication), and the sunshield to protect the payload from direct solar illumination.

The payload had three advanced science instruments: two cameras and a very high resolution spectrometer; their detectors were cooled to temperatures close to absolute zero by a sophisticated cryogenic system.

Primary mirror: 3.5 m in diameter. Herschel’s mirror was the largest ever built for a space telescope mission. The bigger the telescope mirror, the more light it collects; big mirrors mean that we can see fainter objects and we can distinguish fine details.

Launch: 14th May 2009 on board an Ariane 5 from ESA’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. Herschel was launched along with Planck, ESA’s microwave observatory which is studying the Cosmic Microwave Background.

Journey: Herschel separated from the upper stage of the launcher about 26 minutes after launch, Planck followed a few minutes later. The observatory reached its operational orbit about a hundred days after launch.

Orbit: Herschel orbited around a special point in space (called ‘L2’) located about 1.5 million km from Earth in the direction opposite to the Sun. At the end of its operational lifetime, the satellite was propelled into an orbit around the Sun, a little further out than the Earth, where it will remain indefinitely.

Lifetime: Herschel was designed for a minimum of three and a half years (six months of commissioning and performance testing and three years of science operations). It actually lasted for nearly four years before the helium ran out, giving astronomers some additional observing time.

Instruments: HIFI (Heterodyne Instrument for the Far Infrared), a high-resolution spectrometer, PACS (Photoconductor Array Camera and Spectrometer), SPIRE (Spectral and Photometric Imaging REceiver). Together, these instruments covered the range 55–672 microns, nearly a thousand times longer than the wavelength of visible light. Their detectors were cooled to temperatures very close to absolute zero (-273 degrees C).

Launch mass: About 3.4 tonnes.

Dimensions: About 7.5 m high and 4 m wide.

Primary ground station: ESA’s deep space antenna in New Norcia, Australia.

Operations: Herschel worked autonomously for 21 hours per day, following a set of precise instructions uploaded at the start of each observing day. The other three hours were used to communicate with the ground station, sending back the acquired data and receiving the instructions for the next day.