Commissioning: Days 1 – 60 (mid-May – mid-July 2009)

The first two months of Herschel’s life in space were used to check out thoroughly all aspects of the spacecraft and the instruments to make sure everything has survived the launch and works properly in space. For most of this time Herschel was moving steadily away from the Earth, on the way to its final orbit about the L2 point.

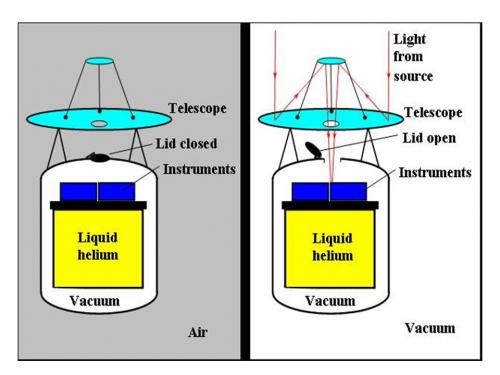

A key moment during commissioning was the opening of the cryostat lid. The instruments are contained in vacuum inside the cryostat, and for testing on the ground, the vacuum was maintained by an airtight lid on the top. Once in space, where there is a vacuum, the lid can be removed so that the light collected by the telescope can get in to the instruments. Removing the lid is a critical operation – if it was not removed successfully, Herschel would not have been able to make any observations because the instruments would not be able to see the sky. Fortunately, this lid was succesfully opened just over a month into the mission (June 2009). The reason it was not done straight after launch is that it took a few weeks for the spacecraft to “out-gas” traces of water in its various materials (inevitable in anything manufactured on Earth). The lid was kept closed while this happened to make sure that none of the evaporating water could get into the cryostat and condense as ice inside the instruments.

The image on the left shows Herschel set-up for testing on the ground before launch. The lid is on, keeping the instruments under vacuum. The instruments can’t actually see the telescope – this will happen for the first time in space when the cover is removed. The image on the right shows Herschel in space after the lid is removed. The light collected by the telescope can now get to the instruments.

This movie shows a test of the lid release mechanism. Once released, it springs back and after a few oscillations it settles in a position that does not block the light collected by the telescope from entering the cryostat and being detected by the instruments. This happened in space about a month after launch. [Credit: European Space Agency]

Performance verification: Days 60 – 150 (mid-July to mid-October 2009)

After everything had been checked out, the three Herschel instruments were put through their paces by making every possible kind of observation and setting up each observing mode to give the best results. The data processing software was also tested and improved where necessary to make sure that the highest quality scientific results are being produced. All of this took three months to complete. Only then was Herschel fully ready for science observations.

During this period, the HIFI instrument suffered a malfunction, now thought to be due to a cosmic ray hitting one of the computer chips and causing an error. This caused the power supply of one of the critical components to be damaged beyond repair. Luckily, a spare unit was on board ready to be used and after a full investigation HIFI is now working again as of January 2010. The control software has been updated so that the same thing won’t if another cosmic ray hits the same part of the instrument. This put it slightly behind schedule relative to the other two instruments, but the HIFI team are working hard to catch up.

Science demonstration: Days 150 – 190 (mid-October – end November 2009)

To show the world what Herschel can do, and to generate some early scientific results, the next six weeks (Days 150-190) were used to make scientific observations covering the whole range of Herschel’s capabilities – a little bit of everything that Herschel can do covering the solar system out to the most distant reaches of the Universe. The results were analysed quickly and presented at a European Space Agency workshop in December 2009.

Routine operations

Herschel is coming towards the end of its life after more than three years of operation. Roughly the first half of the mission was allocated to “Key Projects” – big observational programmes designed for in-depth investigation of some of the main questions that Herschel has been designed to answer. The second half of the mission was made available for smaller programmes and for following up some of the work done during the first part.

End of the mission

The helium in Herschel’s cryostat was depleted at the end of April 2013. It lasted slightly longer than the predicted 3.5 years. After some decommissioning activities, and final measurements, the fuel was dumped, sending the spacecraft away from L2, and it was switched off for the last time. Herschel will orbit the Sun indefinitely, coming close to the Earth roughly once every 13 years, but never close enough to be any danger.