| Basic Information | |

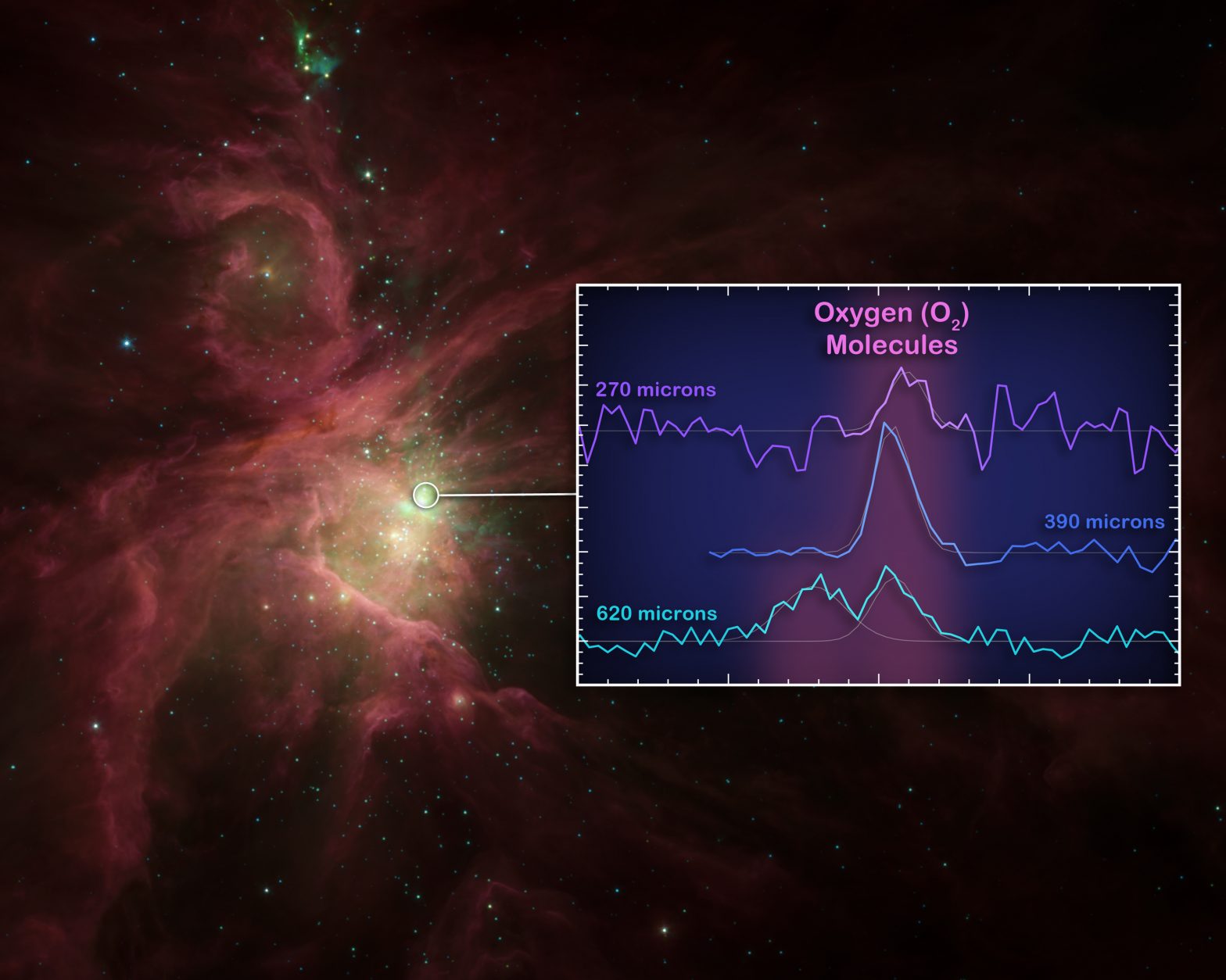

| What is this? | A region of the Orion Nebula, where molecular oxygen has been found in space for the first time |

| Where is it in the sky? | In the centre of the constellation of Orion |

| How big is it? | The Orion Nebua is 20 light years across, but HIFI only looked at a tiny portion of it. |

| How far away is it? | Around 1300 lighte years away |

| What do the colours represent? | The background image shows a view of the Orion Nebula from the Spitzer satellite, at shorter wavelengths than Herschel sees. The red material is gas and dust in the nebula, while the blue-green regions are stars and clouds of dust being heated by them. The lines on the graph show the spectrum of light measured by the HIFI instrument onboard Herschel |

Downloads

See this object in:

Herschel has found molecules of oxygen deep in the heart of the Orion Nebula. While individual atoms of oxygen are known to be relatively abundant, this is the first time that molecular oxygen – two oxygen atoms bonded together – has been found. The lack of detection of molecular oxygen has stumped astronomers for years, but this discovery still leaves a few questions unanswered.

Oxygen is the third most abundant element in the Universe, after hydrogen and helium, and is found in the Earth’s rocks, atmosphere and oceans. As well as being a key ingredient of our planet, it is vital for life on Earth, and we breathe in the molecular form.

Previous satellites, including NASA’s Submillimetre Wave Astronomy Satellite (SWAS) and Sweden’s Odin mission, have both looked for oxygen, but did not detect any. It is thought that the oxygen freezes only tiny dust grains floating in interstellar space and, after combining with hydrogen, is turned into water ice. This makes it much harder to detect, until the dust is warmed and the ice evaporates and the molecular oxygen can form again.

This warming is expected to occur near star-forming cores, such as those deep in the Orion Nebula. An international team lead by Paul Goldsmith, NASA’s Herschel project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, used the HIFI instrument on board Herschel to search for oxygen. HIFI is much more sensitive than the previous intruments, has been used in the past to detect many much more complex molecules in the Orion Nebula. For this study, it was used to look at three particular wavelengths where oxygen is expected to emit submillimetre light.

The Orion Nebula is the perfect place for the team to start their search, as it is the nearest large star forming region to Earth and contains many clumps of dust being heated by stars in the process of forming. The stars forming in the centre of the nebula heat the surrounding gas and dust, and indeed the team found molecular oxygen for the first time – but at the level of just one molecule of oxygen for every million molecules of hydrogen. “This explains where some of the oxygen might be hiding”, commented Dr Goldsmith. “But we we didn’t find large amounts of it, and still don’t understand what is so special about the spots where we find it. The Universe still holds many secrets.”

The search is far from over, and the mystery of where all the oxygen is still lingers on. Göran Pilbratt, ESA’s Herschel Project Scientist, believes this is a breakthrough moment in the ongoing investigation: “Thanks to Herschel, we now have an undisputed confirmation that molecular oxygen is definitely out there. There are still many open questions but Herschel’s superior capabilities now enables us to address these riddles.”

Detailed Information

Gould Belt Survey