| Basic Information | |

| What is this? | A distant galaxy in the early Universe, forming stars over 1000 times faster than outr Milky Way galaxy |

| Where is it in the sky? | In the constellation of Draco |

| How big is it? | The galaxy is only around a twentieth the size of our Milky Way |

| How far away is it? | It is so far away that its light has taken 13 billion years to reach us. We see it as it was when the Universe was only 880 million years old |

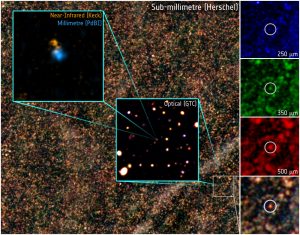

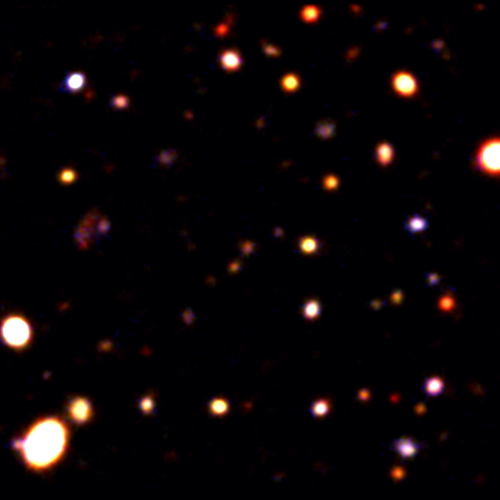

| What do the colours represent? | The redder objects are more distant, and bluer objects are closer to us |

Downloads

See this object in:

Astronomers using Herschel have discovered a distant galaxy that challenges the current theories of galaxy evolution. Seen when the Universe was less than a billion years old, it is forming stars at a much faster rate than should be possible according to existing predictions.

This particular galaxy, known only as “HFLS3”, is so distant that the light we see has taken 13 billion years to get to Earth. We see it as it was when the Universe was only 880 million years old, long before current theories of galaxy evolution predict that such a galaxy should have existed. In the infant Universe, galaxies should have been forming stars at a much slower rate than is observed in HFLS3.

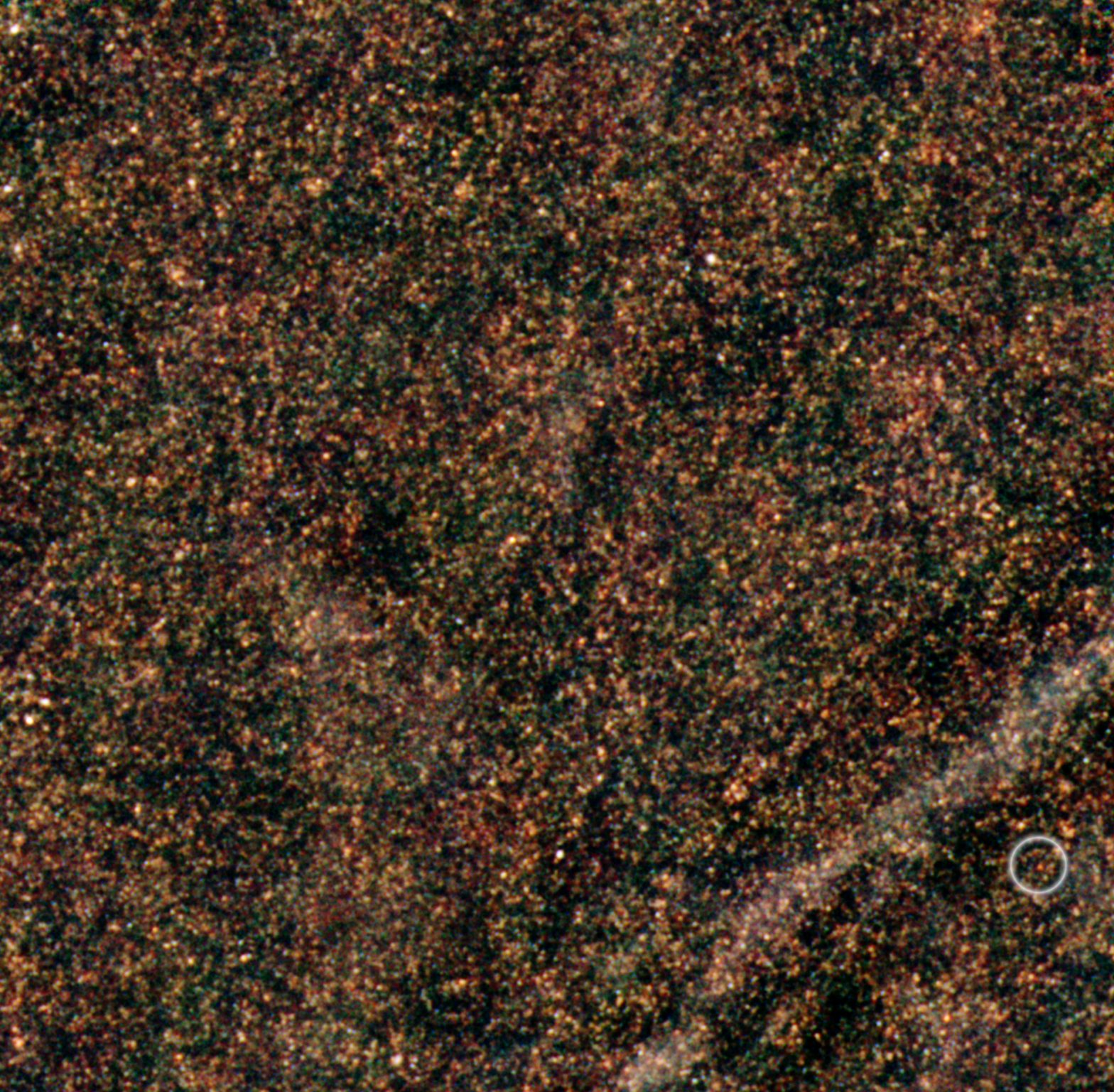

Herschel has been surveying the distant cosmos, finding hundreds of thousands of distant galaxies. By looking at sub-millimetre light, Herschel is revealing how fast these distant galaxies are forming stars, and by determining the ages of the galaxies, astronomers are building up a cosmic timeline of star formation, searching for when the first massive galaxies started churning out stars.

“Looking for the first examples of these massive star factories is like searching for a needle in the haystack, and the Herschel data is extremely rich,” says Dominik Riechers, Cornell University, who led the investigation. “We were hoping to find a galaxy at such vast distances, but we could not expect that they even existed that early on in the Universe.”

The galaxy “HFLS3” was seen as a small red dot in the Herschel images, and its colour is what first intrigued the team. “This galaxy gained our attention because it was bright, yet very red, compared to others like it,” says Dave Clements, Imperial College London. “But while Herschel is great at highlighting these galaxies, we need to use other telescope to investigate further,” he adds.

The first step was to rule out any other effects that could cause the galaxy to look so bright. Using optical and near-infrared telescope, such as the Gran Telescopio Canarias in the Canary Islands and the Keck Telescope in Hawaii, the faint light from a much closer galaxy was seen. Although it lies in almost the same place in the sky, this relatively nearby imposter could not account for the brightness of HFLS3 in the Herschel images.

It was observations with radio and millimetre-wave telescopes, such as the Plateau de Bure Interferometer in the French Alps, which determined that this tiny galaxy, only around one twentieth the size of our Milky Way, is seen at such an immense distance. These additional observations also showed that HFLS3 is incredibly rich in carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, forming compounds such as carbon monoxide, water and ammonia.

“The stars being born in HFLS3 heat up the surrounding material within the galaxy.”, explained Peter Hurley, University of Sussex. “This material contains gas molecules such as carbon monoxide and water, which emit their own unique signatures when heated. By comparing the observations with models, we can gain a better understanding of the conditions within this extreme object.”

Combined with the Herschel observations, these measurements allow the astronomers to deduce that this tiny star factory is producing stars around two thousand times faster than our own Milky Way, making it a type of galaxy known as a “starburst”. Environments like this do not exist on galaxy-wide scales in the Universe today.

“This galaxy is just one spectacular example, but it’s telling us that early star formation like this is possible,” explains Jamie Bock, Caltech, and one of the leaders of HerMES survey which originally found this galaxy.

“We’ve shown that Herschel data can find these extreme examples,” says Seb Oliver, University of Sussex, and the other leader HerMES. “The next step is to sift through the Herschel data more carefully, and try to deduce just how common such galaxies were in the early Universe”, he concludes.

Full field as seen by Herschel.

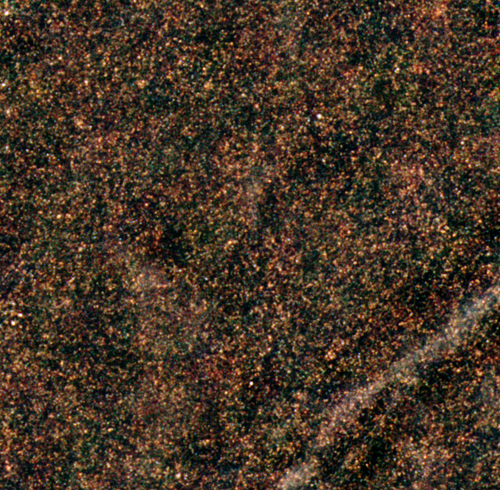

Zoom-in on Herschel image of HFLS3

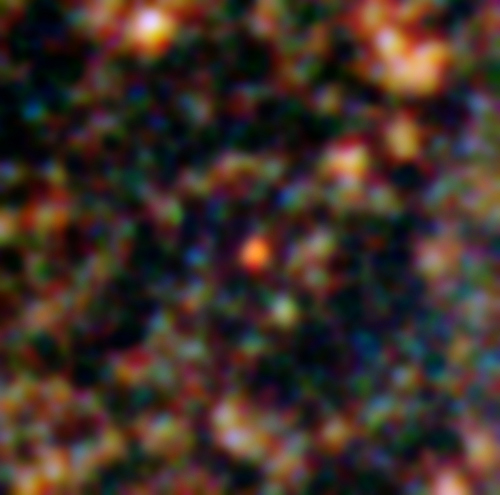

Optical image of HFLS3 (GTC)

Near-IR (orange) and millimetre-wave (blue) image of HFLS3 (seen in mm-wave) and a much closer galaxy, which is seen better in near-infrared light (Keck Observatory/IRAM)