| Basic Information | |

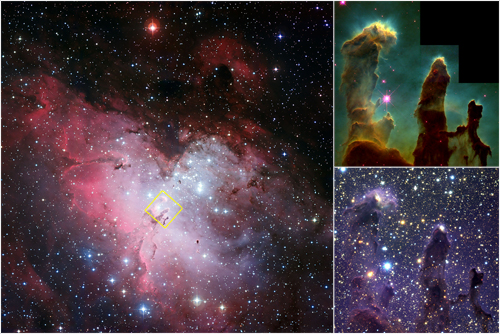

| What is this? | The Eagle Nebula, which contains the famous Pillars of Creation |

| Where is it in the sky? | In the constellation of Serpens, not too far from the centre of our Galaxy |

| How big is it? | The whole image is around 50 light years across, and the pillars are each several light years long |

| How far away is it? | Around 6,500 light years |

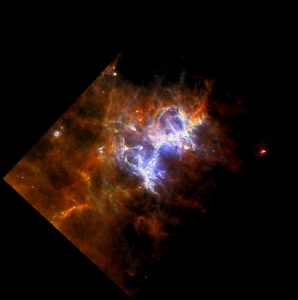

| What do the colours represent? | Bluer material is warmer, being heated by newly formed stars, while the redder regions are colder material much further from the star formation. |

Downloads

See this object in:

The European Space Agency’s Herschel Space Observatory has made observations at far infrared wavelengths toward one of the most iconic images in astronomy: the “Pillars of Creation”. The region around the Pillars in the stunning Hubble Space Telescope image of these three towering pillars of gas and dust, originally taken in 1995, has now been re-observed with Herschel. This region in fact is only a small part of the Eagle Nebula, a star formation region which lies 6500 light years away. The new Herschel observations highlight the processes occurring within the pillars, and the locations of stars that are forming throughout the surrounding area.

The three pillars, made of gas and dust, are each several light-years in length and are at the centre of an incredibly complex region 30-40 light-years across. The pillars are the remnants of a much larger cloud which has been eroded away by a cluster of hot, young stars near the tips of the pillars. The densest pockets of gas and dust, called “evaporating gaseous globules” (or EGGs), resist the erosion, creating the beautiful structures seen here. The EGGs are highlighted

The EGGs are thought to contain very young stars, but views of the region in visible light can only tell astronomers so much. Cold dust, made up of small grains of carbon and silicates blocks out the light from stars within or beyond the pillars, with the only illumination coming from the outer layers of gas that are energised by the intense light from nearby stars. The Herschel Space Observatory, meanwhile, sees far-infrared light, with wavelengths thousands of times longer than visible light. Rather than seeing the pillars as dark silhouettes, Herschel sees the clouds of dust glowing in their own light.

Professor Glenn White, of the Open University and The Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, and a member of the project team working on these data, said “These observations reveal how complicated the formation of stars is. The local environment in the Eagle Nebula is probably very similar to that when our own solar system when formed almost 5 billion years ago – so seeing these images is a bit like using a time machine to look at how our own solar system must have been born. In the Eagle Nebula we are observing the formation of individual stars, as well as seeing the way that that radiation from an earlier generation of stars formed several million years previously can induce new star formation in nearby material in the Galaxy”.

In these false-colour images from Herschel, the bluer material is relatively warm compared to its surroundings, although still only at temperatures in the region of -200 degrees Celsius. The brightest blue and white regions in the far infrared picture show the warmest and densest material, where newly formed stars are heating their surrounding cocoons of dust, and proving that stars really are forming in the EGGs at the tips of the pillars. The redder regions trace much colder material, just a few tens of degrees above absolute zero (-273 Celsius). Frail wisps of cold dust, left over after star formation, can be seen draped across the region.

The bright red and orange regions show the locations of clumps of cold dust that are in the process of collapsing to form stars. Scattered around the area, these show that star formation is occurring far from the central star cluster. Star formation often occurs in regions that are completely obscured from optical telescopes detecting visible light. Professor Derek Ward-Thompson, from Cardiff University, said “Herschel is allowing us to see stars forming in a huge range of different environments: from deep in the centre of star clusters to the cold outer regions of nebulae.”

The Herschel observations are complemented by x-ray observations by the XMM-Newton spacecraft, along with optical and near-infrared observations from the Hubble Telescope and the ESO Very Large Telescope in Chile. These show the incredibly hot gas around the very youngest stars, tracing the bright cluster of already formed stars in the Nebula. The x-ray images have led astronomers to believe that one of the more massive stars in the central cluster may have recently exploded in a massive supernova, creating a bubble of warm gas around the cluster. The optical and near-infrared pictures show how the ultra-violet emission from the central star cluster illuminates, and ionises, hydrogen gas at the surfaces of the fingers.

Prof Mark McCaughrean, from the European Space Agency, said “It’s great to see data from two of our space observatories, operating at almost opposite ends of the wavelength spectrum, being combined to give a spectacular new view of this well-known region, simultaneously shedding light on both the birth and death of stars.”

For more images, including some at additional wavelengths, please see the ESA website.

Detailed Information

HOBYS