| Basic Information | |

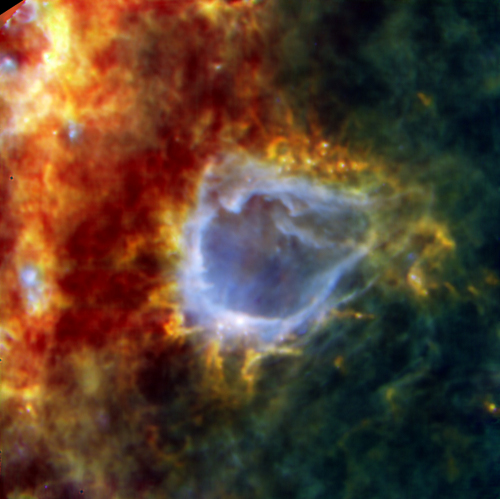

| What is this? | A bubble in space around a massive star, with another massive star forming on its boundary – seen as a bright white object on the bottom of the bubble |

| Where is it in the sky? | In the constellation of Scorpius |

| How big is it? | The bubble is about 10 light years across, and the forming |

| How far away is it? | 4300 light years away |

| What do the colours represent? | Blue is warmer light, heated by the central star (invisible at these wavelengths); red material is cooler. |

Downloads

See this object in:

This image shows a bubble in space known as RCW 120. It lies about 4300 light-years away and has been formed by a star at its centre. Just at the bottom of the bubble is a bright object: an embryonic young star with suprisingly large mass between 8 and 10 times the mass of our Sun. Around the young star there is still enough material to build 2000 stars like our Sun, and so this massive star should only carry on getting bigger and bigger.

Not all of the surrounding material will fall onto the star, even the largest stars in the Galaxy do not exceed 150 times the mass of the Sun. But the question of what stops the matter falling onto the star is a puzzle for modern astronomers. According to theory, stars should stop forming at about 8 solar masses (a solar mas is the mass of our Sun). At that mass they should become so hot that they shine powerfully at ultraviolet wavelengths, pushing away the material and preventing any more accumulating. A prime example of this is the star in the centre of the bubble.

However, we know that this doesn’t always happen as there are much more massive stars in our Galaxy. An example is Eta Carina, weighing in at over 100 solar masses. There are numerous other examples of stars bigger than this theorectical limit – inlcuding the bright star Betelgeuse in the constellation of Orion which is around 20 times the mass of the Sun. Astronomers would like to know how some stars can seem to defy physics and grow so large. Is this newly discovered stellar embryo destined to grow into a stellar monster? At the moment, nobody knows but further analysis of this Herschel image could give us invaluable clues.

The star in the centre of RCW120 is not visible at these infrared wavelengths but pushes on the surrounding dust and gas with nothing more than the power of its starlight. In the 2.5 million years the star has existed. It has raised the density of matter in the bubble wall so much that the quantity trapped there can now collapse to form new stars. This is an example of “triggered star formation”, where stars are born as a result of the presence of a previous generation of stars. Whether a star this large can form on its own is yet to be seen.

Very massive stars are very rare compared to more “normal” stars like our Sun. They also only live for a few million years, burning all their fuel extremely quickly due to the immense temperatures and pressures at their centres. Seeing such a star at such a young stage gives astronomers a unique opportunity to study it and try to revise their theories.

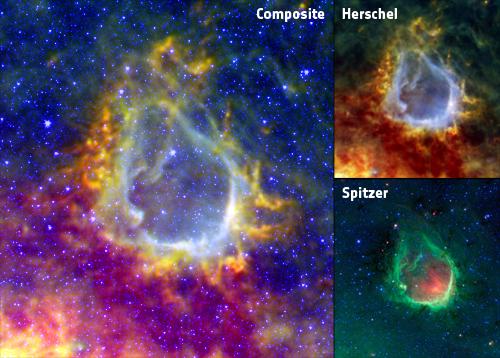

Herschel is an excellent telescope to discover stars like this at a range of stages of their lives, and try to build up a bigger picture of the processes involved in their formation. But much more can be learned by combining it with observations by other telescopes. The image below show the Herschel image combined with one from NASA’s Spitzer satellite.

Spitzer and Herschel both clearly see the ring of material, which is being heated and compressed by the intense ultraviolet light from hot, massive stars in the centre. Seen in the near-infrared by Spitzer, these stars don’t stand out against the background of others seen in the image. The coldest dust is only seen by Herschel in far-infrared wavelengths, and lies around the edge of the ring, seen as red and yellow in this image. The warmer dust in the ring also glows at the shorter wavelengths which Spitzer measures. The shorter wavelengths allow Spitzer to observe the dusty ring in exquisite detail, but do not show the colder dust.

The biggest surprise in the image is the bright white blob on the left edge of the ring. The Herschel measurements show that this is a star in the process of forming, which has already grown to ten times the mass of the Sun. There is still plenty of room for growth, though, and this proto-star could end up being one of the largest in our Galaxy, possibly hundreds of times the mass of our Sun.

Current theories struggle to explain how such massive stars form, but observations by Herschel are allowing astronomers to understand the processes involved. Understanding the role of all the material involved requires observations from many telescopes at a wide range of wavelengths.